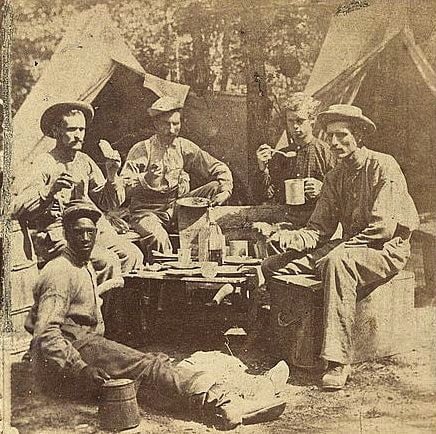

Army of the Potomac – Union soldiers cooking dinner in camp – Library of Congress

We grab our plates and cups, and wait for no second invitation. We each get a piece of meat and a potato, a chunk of bread and a cup of coffee with a spoonful of brown sugar in it. Milk and butter we buy, or go without. We settle down, generally in groups, and the meal is soon over… We save a piece of bread for the last, with which we wipe up everything, and then eat the dish rag. Dinner and breakfast are alike, only sometimes the meat and potatoes are cut up and cooked together, which makes a really delicious stew. Supper is the same, minus the meat and potatoes.

– Lawrence VanAlstyne, Union Soldier, 128th New York Volunteer Infantry

The biggest culinary problem during the Civil War, for both the North and the South, was inexperience. Men of this time were accustomed to the women of the house, or female slaves, preparing the food. For a male army soldier, cooking was a completely foreign concept. Thrust into the bleak reality of war, soldiers were forced to adjust to a new way of life—and eating—on the battlefield.

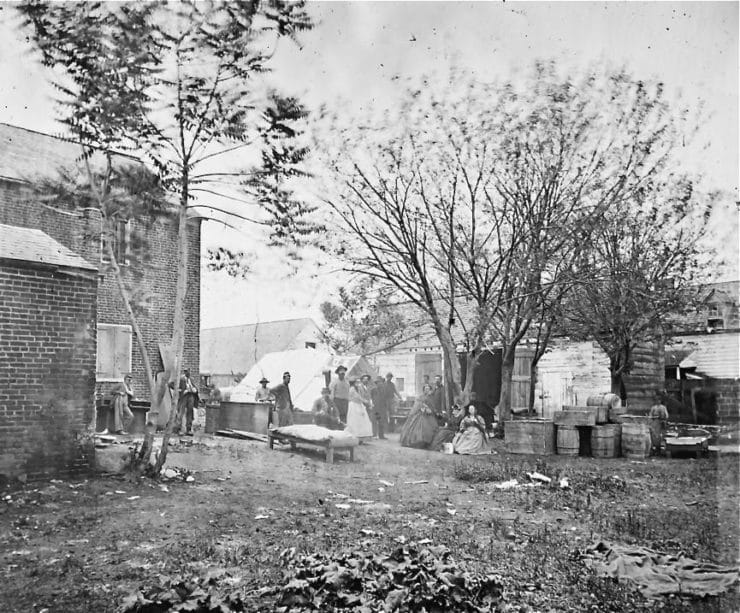

In the early stages of the war, the Union soldiers of the North benefited from supervision by the United States Sanitary Commission. Commonly known as The Sanitary, it made the soldiers’ health and nutrition a top priority. Even before the start of the war, volunteers in The Sanitary were trained to find and distribute food to soldiers stationed in the field. They were expected to be knowledgeable in determining which foods were available during each season, and how to preserve food items for transportation and storage. It was the responsibility of The Sanitary to schedule and maintain a constant supply of food to soldiers at war.

Fredericksburg, VA – Cooking tent of the U.S. Sanitary Commission – Library of Congress

While the Sanitary did their best to provide a reliable supply of food, that didn’t guarantee a tasty or healthy meal. Considering there were nearly 2 million soldiers in the Union army, the Sanitary did not focus on flavor nor variety. It was a large enough task to provide the basics and keep their soldiers from starving. When food deliveries were interrupted by weather delays or other challenges, soldiers were forced to forage the countryside to supplement their meager diets.

Again we sat down beside (the campfire) for supper. It consisted of hard pilot-bread, raw pork and coffee. The coffee you probably wouldn’t recognize in New York. Boiled in an open kettle, and about the color of a brownstone front, it was nevertheless… the only warm thing we had.

– Charles Nott, Union Soldier, 16 yrs. old

At the start of the war, James M. Sanderson, a member of the Sanitary, became concerned with reports of poor food quality and preparation. Sanderson, who was also a hotel operator in New York, believed that his experience would be of value to the Union. With the help of New York Governor Edwin D. Morgan, Sanderson set out to visit soldiers in the field, in hopes of teaching them a few simple cooking techniques. He started with the camps of the 12th New York, as they were deemed “most deficient in the proper culinary knowledge.” He reportedly saw a significant change in just three days.

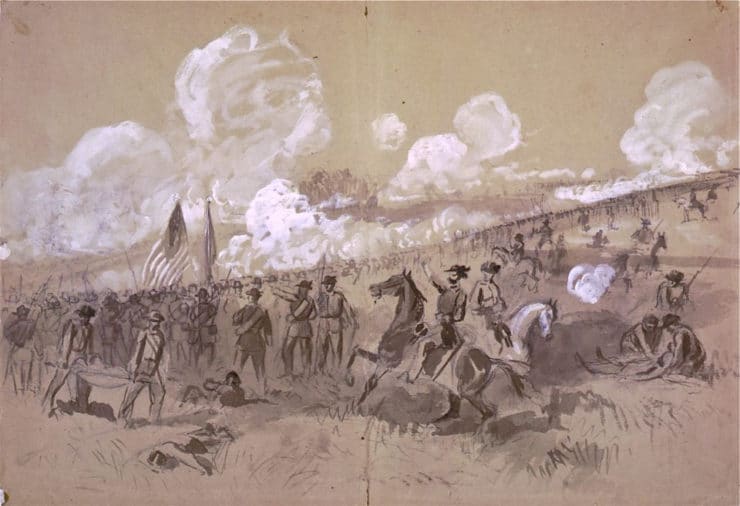

Colonel Burnside’s Brigade at Bull Run – Library of Congress

On July 22, 1861, just after the Union’s loss in the First Battle of Bull Run, Sanderson approached the War Department with a proposal. He asked that a “respectable minority” in each company be expertly trained in the essential basics of cooking. For every 100-man company, the skilled cook would be appointed two privates; one position would be permanent and the other would rotate among the men of the company. The skilled cook would be given the rank of “Cook Major” and receive a monthly salary of $50. It would be the Cook Major’s responsibility to ration the food, prepare it, and delegate tasks to the company cooks. Sanderson had unknowingly proposed his idea at exactly the right time. Washington was faced with the likelihood of the war lasting years, rather than months. The government was actively looking for ways to increase soldier comfort. Sanderson’s proposal reached the Military Affairs Committee of the U.S. Senate. Though they did not follow his instructions specifically, Sanderson did receive a commission—he was named Captain in the Office of the Commissary General of Subsistence from the War Department.

Around this time, Sanderson wrote the first cookbook to be distributed to the military. The book was titled: Camp Fires and Camp Cooking; or Culinary Hints for the Soldier: Including Receipt for Making Bread in the “Portable Field Oven” Furnished by the Subsistence Department. Though his grammar was questionable, Sanderson did describe several techniques, such as suspending pots over a campfire, that made cooking slightly more convenient in the battlefield.

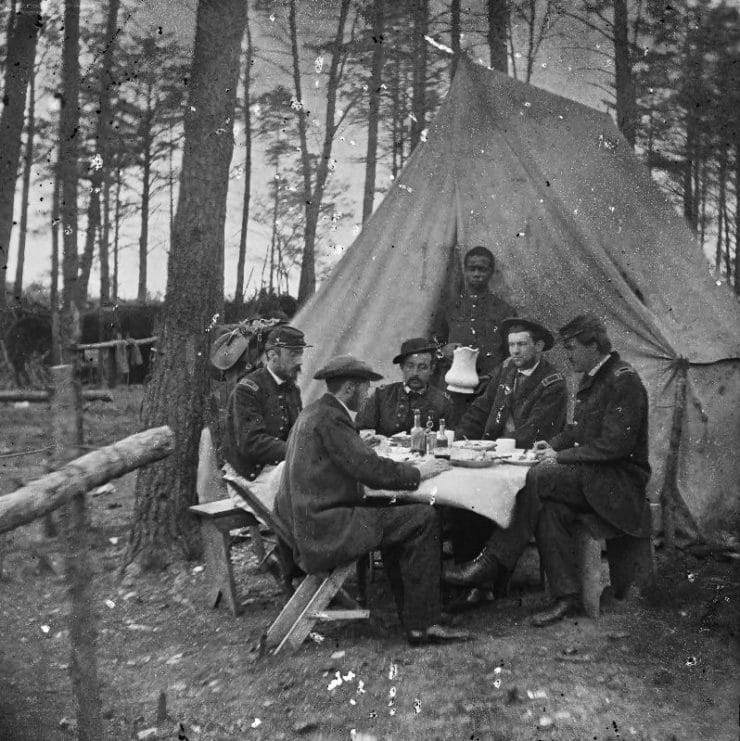

Cooking with a kettle – City Point – West Point, Virginia – Library of Congress

Sanderson believed his efforts were so successful that “no man could consume his daily ration, although many waste(d) it.” This certainly was not the case, as many men still suffered from hunger, illness and death from unsanitary and poorly cooked food. Sanderson did understand the importance of cooking with well-cleaned pots and was quoted as saying, “Better wear out your pans with scouring than your stomachs with purging.”

Typical fare during the Civil War was very basic. Union soldiers were fed pork or beef, usually salted and boiled to extend the shelf life, coffee, sugar, salt, vinegar, and sometimes dried fruits and vegetables if they were in season. Hard tack, a type of biscuit made from unleavened flour and water, was commonly used to stave off hunger on both sides. After baking, hard tack was dried to increase its shelf life.

Dinner party outside tent, Army of the Potomac headquarters, Brandy Station, VA – Library of Congress

An army is a big thing and it takes a great many eatables and not a few drinkables to carry it along.

– Union Officer, October 1863

The following Union army recipe comes from Camp Fires and Camp Cooking; or Culinary Hints for the Soldier by Captain Sanderson. It’s a basic recipe (in those days known as a “receipt”) for “Commissary Beef Stew.” This easy meat stew is thickened with flour and filled out with potatoes and vegetables. The flour and added vegetables allowed Union cooks to stretch small amounts of meat into a substantial, filling meal. While many wartime stews were made from salted preserved meat, this recipe appears to be written for fresh beef. Here is the original recipe, as transcribed in A Taste for War: The Culinary History of the Blue and Gray. Note that grammar and measurements have been clarified from the original source:

Cut 2 pounds of beef roast into cubes 2 inches square and 1 inch thick, sprinkle with salt and pepper, and put in frying pan with a little pork fat or lard. Put them over a fire until well browned but not fully cooked, and hen empty the pan into a kettle and add enough water to cover the meat. Add a handful of flour, two quartered onions, and four peeled and quartered potatoes. Cover and simmer slowly over a moderate heat for 3 ½ hours, skimming any fat that rises to the top. Then stir in 1 tablespoon of vinegar and serve. Other vegetables available, such as leeks, turnips, carrots, parsnips, and salsify, will make excellent additions.

I have adapted Captain Sanderson’s recipe for the modern kitchen; my updated version of the dish appears below. While the stew is simple, it stands the test of time. The long and slow cooking produces exceptionally tender meat chunks. As you cook it, imagine stirring a kettle over an open flame in a Civil War army camp. Hungry soldiers would have looked forward to a hearty stew like this.

Food Photography and Styling by Louise Mellor

Recommended Products:

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Civil War Commissary Beef Stew

Ingredients

- 2 pounds beef stew meat, cut into 2-inch chunks

- 2 tablespoons pork fat or lard (vegetable oil can be subbed to make kosher)

- 3 quarts water

- 4 medium potatoes, peeled and cut into large chunks

- 3 large carrots, peeled and cut into large chunks

- 2 onions, peeled and cut into large chunks

- 2 parsnips, peeled and sliced

- 1 leek, trimmed, sliced, and rinsed clean

- 1/4 cup flour

- Salt and pepper

- 1 tablespoon vinegar

Optional Ingredients

- Chopped turnips or salsify

Instructions

- Sprinkle the stew meat with salt and pepper. Heat the fat in a skillet over medium high heat. Add the meat and sauté for a few minutes, stirring frequently, till well browned, but not fully cooked.

- Transfer the browned meat to a large pot and cover with 3 quarts (12 cups) of water. Bring to a boil. Skim the fat that rises to the surface. Add the potatoes, carrots, onions, parsnips and sliced leek to the pot.

- In a small bowl, whisk together the flour with 1/2 cup cold water till a thick, smooth liquid forms.

- Slowly stir the flour water into the stew pot. Season the pot with salt and pepper (I used 1 1/4 tsp of salt and 1/2 tsp black pepper; use more or less to taste if you prefer). Bring to a boil.

- Reduce the heat a low simmer. Let the stew simmer for 3 1/2 hours, stirring periodically and skimming any fat that rises to the top. If the stew becomes too thick over time, you can add additional liquid to thin it out as needed.

- At the end of cooking, the meat should be very tender and the sauce rich and thick. Remove from heat and stir in the vinegar. Season with additional salt and pepper to taste, if desired. Serve hot.

Nutrition

tried this recipe?

Let us know in the comments!

Research Sources

Davis, William C. (2003). A Taste for War: The Culinary History of the Blue and the Gray. University of Nebraska Press. US.

Herbst, Ron and Sharon Tyler (2009). The Deluxe Food Lover’s Companion. Barron’s Educational Series, Inc., Hauppauge, NY.

Holzer, Harold and Symonds, Craig (2010). The New York Times Complete Civil War. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, New York, NY.

Murphy, Jim (1993). The Boy’s War: Confederate and Union Soldiers Talk About the Civil War. Sandpiper, Boston, MA.

Thank you for this awesome historical recipe! My son made it as an activity when he was studying the Civil War in homeschool. Everyone in the family loved it so much that we’ve added it to list of regular dinners. I make it whenever I find stew meat on sale. Previously, I made a tomato-based stew, but my family prefers this one. I now usually make it in the Instant Pot since it’s ready in about 45 minutes. In the Instant Pot, you can even start with frozen meat. Tastes great with some crusty bread or cornbread. It’s also a versatile recipe in that you can sub whatever veggies you have on hand (I’m sure they did this as well during the war). But I also love the recipe exactly as written. Thanks again.

Thank you for this, Tori! What a fun experience it was to cook this up! I also dug up a turnip from my kitchen garden to add to the stew. I cubed the turnip and sliced the greens and added for the last hour. Everyone including the kids ate.it.up. It was great with the additon of a baguette, but still yummy without. It was also a good history lesson for the kids. I tasted the struggle and all the emotions of rhe American Civil War in that soup. And was reminded that life is still sweet. Given our country’s current political climate, I hope that everyone would taste a bowl of this stew. Eat and remember.

I don’t think that Civil War-era cooks would have skimmed and discarded the fat as fat was hard to come by during war time and was an invaluable source of calories for hard-working, near-starving men-folk. I have a friend raised under harsh rural working conditions in communist-era Hungary and he said they were always starving for fat. I think the soldiers would have sopped up any fat with their bread and that they would have been happy to have it.

Honestly, I thought this post was brilliant. I’m a student and for my A.P. History class we were given free choice on what to do for our Civil War project, and I love to cook so I played to my strengths. I have researched a lot of recipe’s so far, and many have been helpful, but yours is fascinating with the details behind the recipe that will be extremely helpful when it comes to my report! I want to thank you and now I can’t wait to read more recipes and their historical background! Plus this sounds delicious!

If vinegar is used as a meat tenderizer why is it added at the end of the recipe.

I’m not sure it was there to tenderize the meat; this was another reader’s guess. If you’ll read my response to R Lybolt, above, you’ll see my best guesses about the vinegar– though I can’t say for certain why it’s there.

This is a great website. All the features are amazing and I love the historical info and pics. I baked the rugelach and the panko latkes for Hanukah this year and it was the best meal I ever made! The rugelach is fabulous! Everyone thought it was from a bakery and the pancakes were crisp and delic;ous! Thank you! Amy

So glad you’re enjoying the recipes Amy! 🙂

Vinegar is used for making meat tender, as any b-b-q griller can tell you! Love this site.

I love this post for so many reasons. One is that I think the preservation of these recipes and the historical significance of food is a critical and often neglected part of learning about the past. Another is that I was one person lucky enough to dine at America Eats in DC when chef Jose Andres sought to recreate some of our nation’s oldest recipes. And finally, I am from a small town in Georgia and my boyfriend is from just outside Philadelphia. Our Civil War discussions are epic and hysterical. Serving this dish would make our week.

Thanks for this blog and this recipe. I am riveted.

Erin – ekcantcook.blogspot.com

Welcome Erin! 🙂

This is a positively wonderful post! It’s my first time reading on your blog, and I want to tell you how much I’m enjoying it. First read your entry about Martha Washington’s preservation of cherries and now this entry, and I’m astounded. I arrived here after having just finished reading Kathleen Grissom’s The Kitchen House. The description of the various dishes have made want to seek out historical recipes. Thank you so much for what you’re sharing here. I love the whole concept. —Katie Lynne, Astoria, Oregon

Thank you Katie Lynne!

what was the purpose of the vinegar?

Hi R, I’ve read somewhere (I can’t remember where at the moment) that vinegar was used at that time as a treatment for scurvy, which resulted from a lack of fresh vegetables and fruit. It was also used to heal wounds. So perhaps the vinegar was added as a health boost to the stew, though it may also have been for flavor– I can’t say for sure.