Source: Wikimedia Commons

I’m Henery the Eighth, I am,

Henery the Eighth I am, I am!

I got married to the widow next door,

She’d been married seven times before.

And every one was an Henery

She wouldn’t have a Willie or a Sam

I’m her eighth old man named Henery

Henery the Eighth, I am!

Lyrics from the song “I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am” by Fred Murray and R. P. Weston (1910)

History paints King Henry VIII of England as a villainous glutton who hungered for food, women, and violence. But what kind of food satiated this famous king’s infamous appetite? In today’s blog, we will explore the exotic and lavish culinary habits of the British royal monarchy during the 1500’s—a time period known as the Tudor Dynasty. The Tudor family ruled England from 1485 to 1603 with five crowned monarchs; the two best known of these leaders are King Henry VIII (the “wife beheader”) and Queen Elizabeth I (the “Virgin Queen”). Elizabeth’s reign is often referred to as the Elizabethan era, or the golden age in English history. While most of us are somewhat familiar with the history of this time period, very few of us know much, if anything, about what they ate.

This is my first historical food blog that is not directly related to Jewish food. While I’ll still be posting my weekly Jewish recipes, I’ve decided to branch out a bit and explore other parts of food history. I’ve chosen the Tudor dynasty this week because I have a personal connection to it. Recently while I was researching my ancestry, I started to look at the family tree of my paternal great-great-grandmother, Mary Jane Wyatt. After a lot of digging, I discovered that Mary was a direct descendant of Thomas Wyatt, a poet in King Henry VIII’s court.

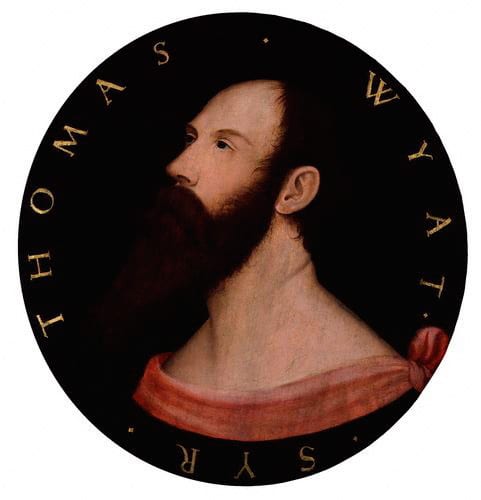

A portrait of Sir Thomas Wyatt, my ancestor. It is reported that he was quite strong and handsome! Source: Wikimedia Commons

I was thrilled to learn that I share a close genetic connection to somebody who is part of Tudor history! Thomas is credited with creating the sonnet form of poetry. He was also briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London for suspected adultery with Queen Anne Boleyn… but that’s a totally different blog. 🙂

There is a lot to cover here, so I’m splitting this time period into two blogs. This first blog will focus on the royal Tudor diet and the foods enjoyed by the upper classes. In a future blog, I will cover the diet of the lower and emerging middle classes in Tudor England. For now, let’s explore what good old Henry himself might have eaten during his reign.

Hampton Court Palace – Surrey, England

If you want to experience royal Tudor cooking first-hand, schedule a visit to Hampton Court Palace, a favorite destination of King Henry and his daughter, Queen Elizabeth. The Hampton Court kitchens have been fully restored as a living monument to Tudor dynasty cooking. In their heyday, the kitchens occupied more than 50 rooms in the palace. A staff of 200 provided two meals per day for the 800 members of King Henry’s court (“dinner” around 11:00am and “supper” around 5:00pm). Cooking for a hungry royal court of this size was no easy task; it required massive amounts of ingredients. A provisioning list from the reign of Elizabeth I reveals the quantity of meat cooked in the royal kitchens annually: 8,200 sheep, 2,330 deer, 1,240 oxen, 760 calves, 1,870 pigs, and 53 wild boar. Most of the meat was hunted on royal land, though some was supplied from the palace’s own pheasant yard and rabbit hutch. Fish for Lent was supplied by the palace Pond Garden. Fruits, herbs, and English mustard were grown and harvested on the palace grounds; more exotic ingredients like spices and citrus were imported from other parts of Europe and the Orient.

The Great Kitchen at Hampton Court Palace

All of this food was prepared in Hampton Court’s Great Kitchen, a massive operation with six large fireplaces and roasting spit-racks. Meals were generally cooked over open wood-burning fires in the Great Kitchen. Meat stocks for soup and boiled meats were cooked in the Boiling House inside a gigantic 90-gallon boiling copper. Delicate desserts and puddings were baked in the Confectionery; pies, both sweet and savory, were baked in the Pastry House.

Meat pies were one of the most popular dishes of the time period, and were enjoyed by both upper and lower classes. Upper class pies were made from fancy pastries of refined flour, often embellished with beautifully decorated pastry shells. When it came to royal cuisine, presentation was everything. The emphasis wasn’t on flavor so much as exclusivity—the rarer and more difficult to obtain an entree was, the more it was valued at court. “Delicacies” such as porpoise meat and grilled beaver tail were served at banquet, sometimes loosely interpreted as “meatless” alternatives for Lent. Food also doubled as entertainment; pies would sometimes conceal live animals like birds or frogs, which would be released when the pie was cut. Roasted meats were often housed in their “original” dressing—for instance, a whole roasted peacock might be dressed in its own feathers, complete with a gold-gilded beak.

Still Life with Peacock and Pie – Pieter Claesz, ca 1627 Source: Wikimedia Commons

While the royal Tudor diet was lavish, it was not at all healthy. Vegetables were considered poor man’s fare, and were only eaten sparingly by the royal court. Raw fruits were almost never consumed; in fact, they were outlawed in 1569 because at that time they were believed to cause illness. In the painting above you’ll notice a bowl of fresh fruits… the artist, Pieter Cleasz, was Dutch and did not share the British aversion to fruits and vegetables. Because of the lack of vegetables and fruits in their diet, many in the upper classes suffered from mild forms of scurvy. In fact, scurvy was so prevalent in London during the 16th and 17th centuries that it led Gideon Harvey, physician to Charles II, to describe it as the “Disease of London.” Enhancing the unhealthfulness of the Tudor diet was the prevalence of fat and sweets. Royal desserts were sweetened with sugar, which was expensive and rare in early Tudor times. The upper classes frequently battled tooth decay because of their increased sugar consumption. Queen Elizabeth herself was known to have quite a sweet tooth.

Manchet—a white bread roll made from finely milled wheat—accompanied each royal meal. This bread was often served with thick slices of marmalade and jellies molded into all kinds of intricate shapes such as castles or animals. Citrus fruits like oranges and lemons were also enjoyed, but they had to be imported and were only reserved for the very wealthy. Spices like nutmeg, cloves, ginger, and saffron were used liberally in Tudor cuisine, as were sauces and garnishes. And of course, a Tudor meal wasn’t complete without a glass of ale to wash it down. Strong, sweet wine was the most popular drink with the royal court, which was stored by the barrel in their many castles across the English countryside. By way of example, about 600,000 gallons of ale were consumed per year at Hampton Court Palace—and that was just one of several English residences for the royal court.

The Well Stocked Kitchen – Joachim Beuckelaer, 1566 Source: Wikimedia Commons

As we can see, the appetite of the Tudor Court was voracious and extravagant. While many items in the Tudor diet (like roasted swan, beef lung, or fillet of porpoise) might sound bizarre or unappetizing to our modern pallets, this time period actually produced some delicious recipes that are still enjoyed today, both in Britain and abroad. One such dish is rice pudding.

Rice pudding has been around for centuries. In the Oxford Companion to Food, Alan Davidson writes:

Rice pudding is the descendant of earlier rice pottages, which date back to the time of the Romans, who however used such a dish only as a medicine to settle upset stomaches. There were medieval rice pottages made of rice boiled until soft, then mixed with almond milk or cow’s milk, or both, sweetened, and sometimes coloured. Rice was an expensive import, and these were luxury Lenten dishes for the rich. Recipes for baked rice puddings began to appear in the early 17th century… Nutmeg survives in modern recipes.

Rice pudding happens to be one of my favorite comfort foods. Last week I recreated a Tudor-style rice pudding in my kitchen. I’ve included the recipe here on the blog for you to try at home. This recipe was inspired by several historical Tudor dynasty cooking manuscripts which are written in “Olde English” (source list below). I’ve also referenced Shakespeare’s play A Winter’s Tale, in which the Clown character recites what seems to be a grocery list for rice pudding:

Let me see: what am I to buy for our sheep-shearing feast? Three pound of sugar, five pound of currants, rice… I must have saffron to color the warden pies; mace; dates none– that’s out of my note; nutmegs, seven; a race or two of ginger, but that I may beg; four pounds of pruins, and as many of raisins o’th’ sun.

Recipes in 16th century England were written very differently than they are today. Here is one example—a recipe for a “Tart of Ryce” from The Good Huswife’s Jewell, a Tudor cookbook for the middle class published in 1596:

To make a Tart of Ryce.

Boyle your Rice, and put in the yolkes of two or three Egges into the Rice, and when it is boyled, put it into a dish, and season it with Suger, Sinamon and Ginger, and butter, and the juyce of two or three Orenges, and set it on the fire againe.

As you can see, ingredient measurements were often not specified. Temperature was also left to the cook, because an open flame could not be controlled in the same way a modern oven can. Cooking times were not always included, and it was assumed that whoever was reading the recipe already knew how to cook, which means that there is very little in terms of detail provided.

In adapting historical recipes, I’ve taken the liberty of assigning measurements, temperatures and cooking times, so you should have no trouble recreating these dishes in your own kitchen. This rice pudding uses historically accurate spices and ingredients that were enjoyed in Tudor times. It is only mildly sweet, gaining most of its sweetness from the raisins and currants. If you prefer a sweeter pudding, add more sugar to taste. Enjoy!

Recommended Products:

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Tudor Dynasty Rice Pudding

Ingredients

- 2 cups dry rice (white or brown - I prefer basmati)

- 1/4 cup unsalted butter

- 1 1/2 cups milk

- 1 1/4 cups heavy cream

- 3 large egg yolks

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1 1/4 teaspoons cinnamon

- 1/2 teaspoon ginger

- 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

- 3/4 cup raisins (black or golden)

- 3/4 cup currants

- Butter or cooking spray for greasing dish

- Cinnamon sticks for garnish (optional)

NOTES

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 350 degrees F. Steam rice until tender according to package instructions.

- While rice is cooking, place raisins and currants into a small pot and cover with hot water. Bring just to a boil on the stovetop, then remove from heat. Let fruit soak in the hot water to plump.

- After rice has cooked, stir in the butter till melted.

- In a mixing bowl, whisk together milk, cream, egg yolks, sugar, cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg. Pour mixture into the rice and stir till combined. Drain the raisins and currants, then fold them into the rice mixture.

- Grease a 9x9 inch baking dish with butter or cooking spray. Pour rice mixture into the dish. Place in the oven and bake uncovered for about 45 minutes until the top of the pudding turns golden brown.

- Serve garnished with a cinnamon stick, if desired. Serve warm.

Nutrition

tried this recipe?

Let us know in the comments!

Tudor Recipe Sources

A noble boke of festes ryalle and Cokery –1500

A Propre new booke of Cokery – 1545

The Good Huswife’s Jewell – 1596

The Good Huswifes Handmaid for Cookerie in her Kitchen – 1594

Research Sources

Davidson, Alan (1999). Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press, USA.

Kiple, Kenneth F. & Ornelas, Kriemhild Conee (2000) The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge University Press.

Meltonville, Marc (2007). The Taste of the Fire, The Story of the Tudor Kitchens at Hampton Court Palace. Historic Royal Palaces, Hampton Court Palace, Surrey, England.

Shakespeare, William (original 1623, reprint 2008). A Winter’s Tale. Oxford University Press, USA.

Trager, James (1995). The Food Chronology. Henry Holt and Company, Inc., New York,

Can I make this the night before and then reheat?

I’ve never been a huge fan of rice pudding…perhaps because I’ve not had homemade? This Tudor-era recipe sounds positively delicious, though. I’m thinking I will definitely have to try it. Thank you.

What an awesome blog and recipe concept. Found this page through google’s first result from searching Where does rice pudding come from. Keep up the great content!

Hi this is very similar to the one my family uses I have changed a couple ingredients to suit my tastes and what I have on hand , like this past Holiday Season I used egg nog and coconut milk in place of the other milks( in equal amounts ) I also prefer basmati and I tossed a cardamon pod or two in ,instead of the ginger

This was a great post. It was well written and it is so nice to see a recipe from the past. God bless you.

This looks fantastic, wonderful post as well. I’m really enjoying your website so far.

Thank you Lyndsay 🙂

The delicious rice pudding recipe you describe featured regularly in my childhood, growing up in Scotland; however it was baked in the oven in such a way that it became firm enough to be cut up into squares. These could be held in the hand and eaten like a piece of cake – a variation of or at least similar to bread pudding.

Just read your rice pudding recipe alongside the Tudor recipe. I think that when the Tudor recipe says to ‘boil the rice’, it means in the milk and egg mixture, as one would with a modern English rice pudding (which uses a short grain pudding rice). To me, this makes more sense with original recipe, as the rice would absorb the rich milk/cream/egg mixture to become really deliciously creamy. Also, the short grain rice, or risotto rice as suggested above, would thicken the pudding.

I am really looking forward to trying it with all the extra spices and orange juice as you suggest. Thanks for the recipe!

I just discovered your blog. Nice!

I am a medieval re-creationist and one of my specialities is cooking from extant sources. I discovered the recipe for the rice tarts a couple of years back, and did my own version of a rice pudding for an event my re-creation group was hosting. I used arborio rice, and made an orange curd (with part lemon juice and part orange juice, as sour Seville oranges are actually what would have been used) with the egg yolks and the listed spices, them mixed the two together. It was served chilled, and was tart-sweet, creamy, and extremely yummy!

Always delighted to happen upon another blogger interested in the history of the food we eat. Thank you so much for all your research and of course, for this timeless recipe. Louise

What made you decided to add milk, cream, nutmeg and dried fruit to the recipe? The Good Huswife’s Jewell does not list any of these ingredients. You will get a completely different product when you use just the ingredients listed the recipe and it does not yield the kind of rice pudding the modern diner recognizes.

Hi Paula, thank you for your question. I do not always recreate historical recipes exactly as they are written. Sometimes, I prefer to create new historically inspired dishes that express the flavors of the time period. Many historical dishes are difficult (if not impossible) to recreate without certain types of kitchen equipment… wood burning stoves, heavy cast iron pots, etc. In addition, some historical recipes provide less than favorable flavor results (after all, we’ve learned a lot about cooking over the centuries!). I am more interested in giving people a hint of the spices, ingredients, and unique flavors of the time period, while also making sure that the dishes are easy to make and tasty to a modern diner. In this case, if you read the blog, you’ll see that my recipe was inspired by several sources, not only “The Good Huswife’s Jewell.” I also referenced similar recipes from “A noble boke of festes ryalle and Cokery,” “A Propre new booke of Cokery,” and even a grocery list from the Shakespearean play “A Winter’s Tale.”

Great post! I love the history of Tudor England. Very interesting time period.

Thanks for pointing me to this blog. Usually I read your blogs but totally missed this one! I really enjoy your recipes, insights, and blogs. My family heritage is from Georgia Russia and eastern Turkey (molokans) so alot of your recipes are similar to what I grew up with and still cookk today. Thank you.