What the Colonial Virginians Ate: Apple Tansey – Learn what the Colonial settlers of Virginia ate and a traditional colonial recipe for Apple Tansey.

I’m revisiting a historical recipe for Apple Tansey. This refreshed version features beautiful new photographs by my talented friend Kelly Jaggers.

The first colonial settlers came to America for a variety of reasons… money, religious freedom, a new beginning. All undoubtedly had dreams of finding a better life in the New World. It was the birth of our nation, and also the birth of American cuisine.

In 1607 the first British colony—Virginia—was established, and 1776 was the year the Declaration of Independence was signed. This span of years is known as the Colonial Period. It was during this time that large numbers of European settlers began to arrive in the U.S., colonizing along the east coast of North America. There were many different cultural influences in America at the time, including settlers from Europe, slaves from Africa, and Native American tribes. This melding pot of humanity resulted in many diverse approaches to food. To find some perspective in what would otherwise be a massive subject, today I am focusing specifically on the Colony of Virginia, one of the thirteen original British colonies.

Why Virginia? I’m glad you asked! A few years back I put a lot of work into researching my ancestry. Well, it turns out there are some fascinating characters in my family tree. In my What the Tudors Ate blog, I wrote about my ancestor Sir Thomas Wyatt, a poet in King Henry VIII’s court. Wyatt’s offspring did some pretty interesting things, too. He had a son, known as Thomas Wyatt the younger, who led a rebellion against Queen Mary I (the daughter of Henry VIII and heir to his throne).

Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger Source: Wikimedia Commons

Thomas the younger, it is written, had a “wild disposition” and a deep hatred for Spain. When Queen Mary was betrothed to Philip of Spain, Thomas conspired against the marriage, believing that Mary’s younger sister Elizabeth should be on the throne instead. He led a rebellion of 4,000 men who marched on London, but his rebel army deserted him at the last minute, and he was forced to surrender. He was later tried, found guilty of treason, beheaded and quartered as ordered by Queen Mary, aka “Bloody Mary.”

Shivers.

This might well have been the end of the Wyatt family (which means I would have never been born!), but as luck would have it Thomas the younger and his wife had a son before he was executed. That son, George Wyatt, and his wife gave birth to two sons—Reverend Haute Wyatt (1594-1638) and Sir Francis Wyatt (1588-1644). Those two brothers, Francis and Haute, arrived in America on August 1, 1621 aboard a ship called the George. Shortly thereafter, Sir Francis became the first English crown governor of the Colony of Virginia in 1621. He also introduced the first written constitution for an English colony. This constitution became a model for all later forms of government in the American colonies.

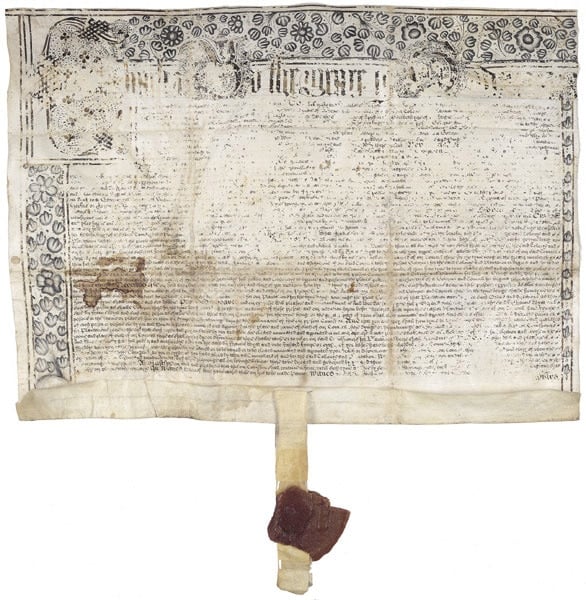

This document was issued by King Charles I on January 11, 1638, and commissioned Sir Francis Wyatt (1588–1644) royal governor of Virginia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

So it seems I am a direct descendent of Francis’ brother, Reverend Haute. I am what some might call an American “mutt,” with many different global regions in my family tree. This Virginia connection is both fascinating and troubling… Virginia’s history of slavery, and the way Native Americans were mistreated when the colonies were founded, leaves me with many questions. I’m still learning about the complexities of my heritage, as I discover more and more about my family roots.

The Colony of Virginia was actually the first permanent English colony in North America, founded at the settlement of Jamestown in 1607. The first decade of colonial life was fraught with hardship as settlers learned to live in this strange New World. European crops would not grow, provisions were poor, and settlers did not know how to fend for themselves in this harsh, uncharted land.

Over time, the new Americans learned from the Native Americans, adopting native crops like maize (corn), beans, squash, cranberries, sunflower seeds, and chestnuts. Wild-growing foods were also gathered and consumed, including berries, grapes, onions and plums. As decades passed, European crops were imported and successfully cultivated in America, including rye, wheat, oats, cabbage, peas, carrots and beets. Orchard fruits flourished in the New World, particularly apples. Apples were eaten fresh, baked into pies and tarts, dried, or fermented into alcohol (“apple jack”—aka apple brandy).

In the early colonial period, settlers relied on fish and wild game (deer, buffalo, wild fowl) to sustain them. Fish from rivers and shellfish from the coast provided an abundant source of protein. As farms were established, cattle were imported and poultry was domesticated. But the most widely consumed meat animal was the pig. Pigs thrived in the South, and were particularly useful to the settlers because their meat was easy to salt and preserve. Lard was often used as a cooking fat. As colonists grew their domesticated animal herds, dairy farming became more popular. Cheese, butter, and eggs became staples of the colonial diet.

Virginia, a plantation colony, has a terrible history of slave trade. African slaves made a major contribution to the Southern colonial diet. Slaves were often permitted to grow their own gardens to supplement their food rations. In these gardens they cultivated a variety of then unfamiliar foods, including yams, okra, peanuts, melons and sesame seeds. These foods were adopted by the mainstream, and quickly became popular throughout the American South.

In the colonies, three meals were served per day—breakfast in the morning, dinner mid-day (the most substantial meal), and a light supper in the evening. Of course, different income brackets enjoyed different types of food depending on what they could afford. The diet of Governor Francis Wyatt would have been quite different from the poorer colonial settlers and slaves. But even the wealthy and well-established had to plan their meals around what was readily available to the colonies. Very few food items were imported, particularly in the early colonial period.

The best descriptions I’ve found about colonial eating appear in a book published in 1975 called A Cooking Legacy by Virginia T. Elverson and Mary Ann McLanahan.

BREAKFAST

In frontier outposts and on farms, families drank cider or beer and gulped down a bowl of porridge that had been cooking slowly all night over the embers… The southern poor ate cold turkey washed down with ever-present cider. The size of breakfasts grew in direct proportion to growth of wealth… It was among the Southern planters that breakfast became a leisurely and delightful meal, though it was not served until early chores were attended to and orders for the day given… Breads were eaten at all times of the day, but particularly at breakfast.

DINNER

Early afternoon was the appointed hour for dinner in Colonial America. Throughout the seventeenth century and well into the eighteenth century it was served in the “hall” or “common room.” While dinner among the affluent merchants in the North took place shortly after noon, the Southern planters enjoyed their dinner late as bubbling stews were carried into the fields to feed the slaves and laborers… In the early settlements, poor families ate from trenchers filled from a common stew pot, with a bowl of coarse salt the only table adornment… The stews often included pork, sweet corn and cabbage, or other vegetables and roots which were available…

SUPPER

…supper was a brief meal and, especially in the South, light and late. It generally consisted of leftovers from dinner… In the richer merchant society and in Southern plantation life, eggs and egg dishes were special delicacies and were prepared as side dishes at either dinner or supper.

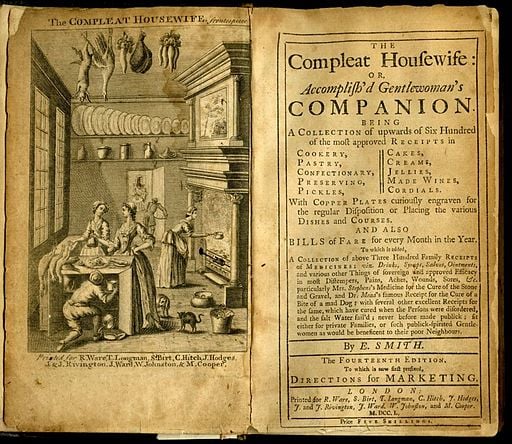

Speaking of eggs and egg dishes, how about we take a taste of colonial life by preparing an Apple Tansey! This historical recipe appears in The Compleat Housewife: Or, Accomplished Gentelwoman’s Companion, a cookbook written by Eliza Smith, originally published in 1742. Though the book was published in London, it was later reprinted and published in Williamsburgh, Virginia by the printer William Parks. It is the first cookbook ever to be published in the United States.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Here is the recipe exactly as it appears in the manuscript:

To make an Apple Tansey,

Take three pippins, slice them round in thin slices, and fry them with butter; then beat four eggs, with six spoonfuls of cream, a little rosewater, nutmeg, and sugar; stir them together, and pour it over the apples; let it fry a little, and turn it with a pye-plate. Garnish with lemon and sugar strew’d over it.

I got super excited when I read this recipe. It was a totally new one to me. Eggs, cream, sugar, and apples. Yum! How can you go wrong??

For our purposes, I have taken the recipe and “translated” it, so you can try a bit of colonial cooking in your kitchen. Pippin apples aren’t available to me locally, so I subbed Granny Smiths, which are tart and firm like Pippins. If you can find Pippins, by all means use them! Rosewater can be purchased at a Middle Eastern market; if you can’t locate a bottle, you can leave it out, as the flavor is quite subtle.

I have to admit, I had a little trouble with this tansey the first couple of times I cooked it. Because of the sugar in the apples and the egg mixture, the bottom of the tansey browns much faster than the top. Adding a lid to the skillet didn’t help much. I finally decided to finish it by broiling the top of the tansey towards the end of cooking. This resulted in a perfectly cooked, perfectly beautiful apple tansey. The colonial settlers didn’t have broilers, obviously, so if you prefer you can flip the egg mixture over like an omelette to cook the opposite side. This will ensure even cooking throughout. Nobody wants a runny apple tansey!

This dish is delicate – light and fluffy. The apples add a subtle sweetness, complimented by the tartness of the fresh lemon juice. It likely would have been served as a side dish at a Colonial dinner or supper. It’s not quite sweet enough to be considered dessert. I think it would make a wonderful addition to a weekend brunch or tea party menu. Sub lowfat milk for cream and your favorite low-cal sweetener for sugar to make a healthier low-carb version. Enjoy!

Food Photography and Styling by Kelly Jaggers

Recommended Products:

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Apple Tansey

Ingredients

- 2-3 apples

- 3 tablespoons unsalted butter

- 4 large eggs

- 2 tablespoons heavy whipping cream

- 2 teaspoons rosewater

- 1/4 teaspoon nutmeg

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- Granulated or powdered sugar for garnish

- Fresh lemon wedges for garnish

NOTES

Instructions

- Preheat your oven’s broiler. Core the apples with a coring tool...

- then slice them into thin rounds. I left the skin on the apples because the recipe doesn’t specify to “pare” them. If you prefer, you can peel the apples before slicing.

- Melt the butter over medium heat until hot, being careful not to let the butter brown or burn. Add apple slices to the skillet. Fry them for about 5 minutes, turning once, until they soften and begin browning at the edges.

- While apples fry, beat the eggs together with the cream, rosewater, nutmeg, and 2 tbsp sugar.

- When apples are ready, pour the egg mixture evenly over the top of the apples. Cook the tansey for about 3 minutes till the bottom solidifies.

- Place skillet in the oven under the broiler. Let it cook for 2-3 minutes longer till the egg mixture is cooked through. Use an oven mitt to remove the skillet.

- Turn the apple tansey onto a large flat plate. Sprinkle it with sugar and splash it with fresh lemon juice. Serve garnished with lemon wedges or sliced lemon rounds, if desired.

Nutrition

tried this recipe?

Let us know in the comments!

Research Sources

Elverson, Virginia T. & McLanahan, Mary Ann (1975). A Cooking Legacy.

Walker & Company, New York., NY.

Harbury, Katharine E. (2004). Colonial Virginia’s Cooking Dynasty.

University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, South Carolina.

Smith, Andrew F. (2007). The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink.

Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Colonial Recipe Sources

Glasse, Hannah. (1747). The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy.

Reprinted by Applewood Books in 1997. Bedford, MA.

Randolph, Jane (1743). Jane Randolph Her Cookery Book

(referenced in Colonial Virginia’s Cooking Dynasty)

Smither, Eliza (1742). The Compleat Housewife: Or, Accomplished Gentelwoman’s Companion.

London, England.

I made this for our 4th of July celebration this year—my son-in-law challenged me to make a colonial dessert from 1776, so I googled and found your website and recipe. It was a big hit—even the grandchildren loved it and are now asking for it again! It just might become a family favorite!! ☺️

I came across your blog while looking for colonial recipes. Interestingly I also descend from Wyatt’s. My mother was born a Wyatt and we are also related to Reverend Haute Wyatt and Thomas Wyatt. We are related ?. Possibly still have shared DNA this far down the line!

That’s very cool Melanie! 🙂

You may want to look at the following for further information on the origins of an Apple Tansey:

The Compleat Cook

Expertly Prescribing The Most Ready Wayes, Whether Italian, Spanish Or French, For Dressing Of Flesh And Fish, Ordering Of Sauces Or Making Of Pastry

Author: Anonymous

Printed by E.B. for Nath. Brook , at the Angel in Cornhill , 1658

Pare your Apples and cut them in thin round slices, then fry them in good sweet Butter, then take ten Eggs, sweet Cream, Nutmeg, Cinamon, Ginger, Sugar, with a little Rose-water, beat all these together, and poure it upon your Apples and fry it.

As you will see, this recipe is from an earlier period and has the addition of ginger.

A copy of the book can be found on Gutenberg.net

Thank you Lincoln!

Hi I used this for a school project, and put it on my blog, of course giving you credit and changing cream to milk.

I made this with my homeschooler during our unit on Colonial times. It was neat to taste the history. Thank you for the idea.

me too ashley! can’t wait!

thanks so much! i am using this recipe for a school project about virginia cant wait to get cooking! 🙂

Columbia Gorge in Oregon (or Washington), has Newtown-Pippins, seasonally. I used to order them for my co-op, especially happy because they are an heirloom that was bred in Queens, NYC.

@Christine – I’m not sure what conditions were like in Virginia, but I know that in colonial Massachusetts, farmers could produce three times as much corn as wheat per acre. Wheat was just too expensive for most folks to use until after the Erie canal was built, and wheat could be imported from New York state (which seems to have had a better climate for wheat).

Rosewater was a standard flavoring before vanilla extract became commonly available, so you could make that substitution.

And it’s gluten-free!! Not that common for me to see a recipe like this online and actually be able to try it. I’ll have to look for more early colonial recipes if it took them a while to import/cultivate wheat. Thanks for a lovely article!

Glad you enjoyed it Christine, hope you get a chance to try it! 🙂

I’m gong to make this too.

But, I think you made to much work for yourself. “let it fry A LITTLE, and TURN IT with a pye-plate” are instructions for flipping, not serving. I know you mention this at the bottom of the paragraph and I’m still wondering why you didn’t attempt a flip as the original instructions state.

Hi Lane– I did in fact try to flip it using a pie plate the first few times I cooked it (should have mentioned that in the blog). The trouble is it’s a very large and thick tansey, which makes it tough to turn/flip without ruining the beautiful shape. Broiling ended up being the easiest solution for cooking the dish evenly. If you prefer you may certainly flip it instead, as I’m sure that is what is meant by the original recipe. Enjoy your tansey! 🙂

I have loved your blog for a long time. I am a shiksa trying to impress my boyfriend with my cooking skills. I also am from Virginia and I just loved reading this article, I can’t wait to try out the Apple Tansey recipe but I am making ruggies today!

I remember my Mother who was from the South her self (Louisiana) use to make this

I haven’t had this in a Long time I can’t wait to make it my self ,

This whole idea of Historical Cooking would make a great TV show and this Colonial Apple Tansey a great episode. 🙂

Check out this Colonial Jewish Cookbook

http://www.amazon.com/Jewish-Cookery-Book-Esther-Levy/dp/1557091099#reader_1557091099